Part One: Foreign lies and Policies

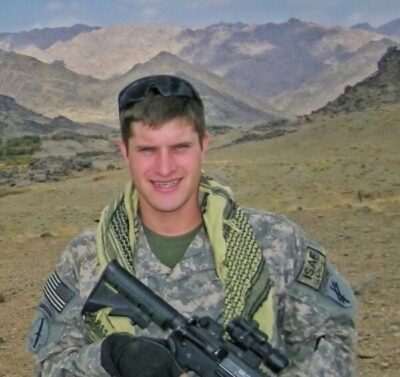

The following piece is written by a brave patriot and partner of the Magic Valley Liberty Alliance.

I want to share some very personal information and experiences I had while serving in the United States Army.

I served for over thirteen years. During my tenure in the service of our great nation I bore witness to the fall of Iraq in 2003. While an infantryman, I witnessed the collapse of the Iraqi infrastructure, government, and rule of law. Iraq became a place of anarchy under martial law. During my time in Iraq I took part in many operations which left me emotionally and mentally scarred for life.

Under Major General David Petraeus, my Rules of Engagement explicitly stated, “Any young man wearing military style-boots is the enemy: shoot to kill. Anyone trying to damage or destroy military property is the enemy: shoot to kill.” I went from killing the “enemy” to employing an authoritative and despotic rule of law under military oversight. The Iraqis didn’t have a constitution to protect them from unreasonable searches and seizures. They weren’t afforded trials or due process of law. They weren’t allowed to speak out freely because they feared reprisal and retaliation by the military.

We used force to enter homes in the middle of the night, round up everyone in the home with a barrel of a gun pointed at them, and then rip through their personal belongings — with little to no regard for these people, their possessions, or their privacy. It became a witch hunt (based on bad intelligence) looking for contraband (weapons and ammunition) and possible intelligence. Too many of us service members thought Iraqis were uneducated, illiterate, and subhuman (the epitome of racism). The Iraqi people didn’t have a place to go to make a redress of their grievances because it fell on the deaf ears of the bureaucracies within the military. One such bureaucracy was the line unit Company Commanders who were in charge of an area of operation, and who were too young, naïve, and ignorant themselves to understand the magnitude of their actions.

I got out of the infantry in 2004 (the moment I had the opportunity) because my actions in Iraq went against the morals and values I was taught and believed. I didn’t get out of the military, though. Instead, I decided to reclassify and change my job in the military. I became a Civil Military Operations (CMO) Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) in 2006. Through this new job working for the US Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command (USACAPOC), I thought I could be a force for good in the world and could right the wrongs I had been a part of in Iraq.

I spent two years in Afghanistan (2006 and 2009) as a CMO NCO on a Provincial Reconstruction Team. I spent nearly every day “outside of the wire“ working with local nations, District Chiefs, and Provincial Governors. I worked directly with the Department of State, USAID, USDA, kinetic military Commanders, UNICEF, and many other Non-government organizations (NGOs). My whole purpose was to build infrastructure, governance capacity, provide humanitarian aid, and keep civilians away from kinetic operations (talking points I was given to recite verbatim when dealing with the media).

During my time working in CMO, I learned a lot about how Afghanistan’s government functioned, and how corrupt the government can become when it is not ruling through the consent of the governed. I was ignorant in many regards to the job I was performing. The majority of the service members conducting Civil Military Operations, including the command, had little to no experience in human and urban geography (nation building), or the complexities of the Afghan hierarchy and culture. I fed into the lies and propaganda by military senior leadership, that I was doing wonderful things for the Afghan people by changing their hearts and minds.

It wasn’t until I started to notice the copious amounts of U.S. tax dollars being spent on fruitless and meaningless projects and programs, that I began to realize how corrupt the U.S. Administrative State really is. During my second deployment I was getting letters from family and friends who had lost their businesses, their homes, and their livelihoods in the 2008 recession. Meanwhile, I felt guilty knowing I was shoveling money out to fund corrupt Afghans and their projects for the sole purpose of emboldening unelected Afghan politicians and their centralized government, while providing field-grade military officers with command time and bulletin points on their Officer Evaluation Reports.

The moment I read the resignation letter of my former Department of State colleague and friend Matthew Hoh, my eyes were opened. Matthew Hoh was a decorated Marine Corps Officer who served in Iraq, and left the Marine Corps to go work for the Department of State. Matthew resigned from the Department of State because he knew Obama’s surge into Afghanistan was futile and was only going to cause more pain and suffering for both coalition forces and the Afghan people. In his resignation letter, he was able to articulate and convey the sentiments that most of us on the ground were thinking in private, but were too afraid to say aloud for fear of retaliation for insubordination.

Sure, there was the occasional puff piece produced by the media describing humanitarian efforts: the schools and roads being built, or the ribbon cutting ceremonies for grand and lavishly furnished government facilities. The reality was that most of these Afghan politicians were not elected by the people, but appointed by the Afghan President and parliament. Nearly all of these Afghan politicians had family ties and/or access to Afghan politicians, NGOs, or foreign diplomats. The Afghan people hated these unelected bureaucrats. The people never asked for roads, schools, or other government-funded programs. They never asked for the centralized form of government forced upon them.

Afghan citizens would come to my base to speak with me and my senior leadership, pleading for assistance, while offering to provide part of the costs for projects that would benefit their village — like renting a backhoe to clear silt out of irrigation canals, so the following year they could get water to their crops. Village elders would go to all of the families in the village asking for donations to raise the capital needed to fund their own projects. I was taught in my training to encourage and support this type of behavior because these people were willing to put their own money on the line and take the risk. They just needed a little extra help and, in the process, we could create a new ally. These rare cases were turned away by my senior command, and the village elders were told to go to their respective government officials and ask them for help. The problem is the Afghan people did not believe or support the puppet government installed over them.

Meanwhile, these same government officials, who were supposed to be representing the Afghans, had their focus on my senior leadership for guidance and monetary funds. They would demand my senior leadership provide them with money to fund their own selfish priorities, which they placed at the top of their short term and long term Provincial Developmental Plans. They would demand my command provide the funds to build lodging for their private security, private housing for staff under their administration, armored vehicles and weapons, or to award certain building contracts to one of their relatives or friends. I used to call these Provincial Developmental Plans “a unicorn-rainbow wish list” because their priorities were outlandish and rarely focused on the Afghan people.

So-called humanitarian aid

Humanitarian aid was a huge issue in Afghanistan. Commanders loved to provide humanitarian aid because it was an opportunity for them to obtain media recognition with a photo op and puff piece to fuel their arrogance and narcissism. After all, who doesn’t like humanitarian aid? You get to give out free stuff and it makes everyone feel so good about what they are doing.

Too often humanitarian aid was not given to people in crisis (flood, famine, drought, pestilence), but given out to random villages, which impacted their local economies. Many times humanitarian efforts artificially inflated and flooded local markets with things like beans, rice, sugar, flour, or tea. The laudable humanitarian efforts impacted the farmers on the outskirts of the villages who worked painstakingly all year to produce wheat, beans, rice and other commodities. These farmers could no longer sell their products at a competitive market price. Many times these farmers lost money, making them very desperate to provide for their families, especially in the winter months when attrition rates were at their highest.

I was ordered to provide humanitarian aid to a village coalition forces hadn’t been to before. This particular village did not welcome us or want the humanitarian aid we offered. The villagers were stand-offish, and I was told by a villager that if they accepted the humanitarian aid the Taliban would come to the village after we left, confiscate all of the aid, and kill any villager who had accepted it. I was ordered to drop off the humanitarian aid regardless, and I was devastated and heartbroken when I discovered that what I had been warned about had happened.

Aiding Afghanistan’s enemies

Hakim Taniwal was the Paktia Provincial Governor I worked with during my first deployment to Afghanistan. Taniwal and his family were exiles who fled to Australia in the 1990s to escape the extremist ideology of the Mujahedin. He returned to Afghanistan in 2002 and was appointed by the Kharzi administration as the first Provincial Governor of the Khost Province. Under the Kharzi administration, he moved on to become the Minister of Mines, and eventually he became the Governor of the Paktia Province. Governor Taniwal was hated by the Afghan people. On September, 10, 2006, I was involved in a mass casualty event in the Paktia Province. A suicide bomber assassinated Hakim Taniwal right outside of the Governor’s mansion which was located next to the Gardez hospital.

There was so much carnage that day. My team along with the medics and doctors at my base grabbed all of the medical supplies we had available and headed to the Gardez hospital. We started a triage to help the overwhelmed medical staff at the hospital. I was there to help provide security, but instead I helped clean up the limbs, appendages, and indistinguishable body parts which littered the street.

The violence did not stop there. The Afghan people hated Taniwal so much they attacked the motorcade carrying his coffin to the burial site and blew it up with a suicide bomber.

Promoting communist pet projects

Life was not easy in Paktia Province. The Kharzi Administration appointed a new temporary Governor, Rahmatullah Rahmat (a communist), while the Afghan parliament looked for a new replacement. The hostilities grew more frequently, and the province became much more dangerous for the coalition forces and the Afghan government officials. Because of what happened to Taniwal, the new temporary Governor Rahmat would not leave the governor’s mansion without a heavily armored coalition forces escort, and he insisted on being in an American vehicle. Governor Rahmat continued pushing my senior leadership for the same unicorn-rainbow wish list as his predecessor. This new governor wasn’t naive or stupid. He knew how to play the system and he played my senior leadership like a fiddle because he was a former employee of several international NGOs. He was the area supervisor in Nangarhar Province for the International Rescue Committee, a field assistant in Farah Province for the International Organization for Migration, and was a senior political assistant for the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan.

He wanted schools built in hostile territories. The U.S. taxpayers funded these projects while my team oversaw the construction of these schools, only to have these schools bombed and destroyed upon completion. He would then ask for these schools to be rebuilt, which my command was more than happy to oblige, only to have them destroyed again.

He wanted a madrasa built – a secular or religious educational institution. Madrasas were foreign to Afghans, but well known in Pakistan – typically known for teaching doctrines that radicalize Muslims. He got his way, and American tax dollars paid for it.

As my unit was getting ready to leave Afghanistan in 2007, Governor Rahmat demanded my commander purchase land so a university could be built in Gardez City. The plan was that the provincial governors in the region would work with each other to develop a plan to allocate the resources to build the university. My team fought with our command on this issue, arguing that if we bought the property, the moment our replacements were gone this man would demand the new commander provide the resources and capital to build his university, insisting the previous commander had promised to build it. Governor Rahmat knew he would be able to exploit the next commander’s ignorance, at the taxpayers’ expense.

“Government knows best” turned villagers violent

The corruption of the Afghan government and coalition forces we were supporting were condemned by the Afghan people. More draconian edicts and measures were implemented to mitigate the loss of property and life. Those measures only emboldened the Afghans to adapt and revolt –becoming more desperate and radicalized in their efforts.

The Afghan government along with the coalition forces vilified and generalized Afghans as being insurgents and terrorists. The majority of vilified Afghans were not terrorists or insurgents, but farmers, shop owners, laborers, contractors, and nomadic sheep and goat herders. They were desperate and were fighting for their sovereignty, traditional values, and their way of life. The Afghan people were afraid to petition for a redress of their grievances because they knew they would be ignored, further vilified, or punished.

The Afghan people turned to violence because they weren’t a part of the decision making processes. The Afghan people did not want a centralized government because they are a tribal people. Day to day life revolved around the family structure, and religious beliefs. Laws, enforcement, and justice were all determined by the Village Elder. Yet the coalition forces and the Afghan government had the hubris to claim “government knows what’s best” and the audacity to push a centralized government upon them, without their consent.

The United States has been in Afghanistan for nearly twenty years with very few results, at a cost of over 2,400 American lives, over 71,000 Afghan civilian lives, and a price tag of 2.26 trillion dollars (not including the obligation to the lifetime of care for Veterans who served in Afghanistan). Systemic failures embedded in our failed foreign policy, bureaucracy of government agencies, and lackadaisical oversight by the Senate and House Armed Services Committees have left Afghanistan in disarray, and the United States more vulnerable to terrorist attacks than we were prior to September 11, 2001.

Over the years I have noticed subtle similarities between what I saw in Afghanistan and Iraq and what I have seen after returning home. COVID-19 has made those subtle similarities abundantly clear: gross hypocrisy, censorship, bureaucracies dictating policy, and the wasteful spending sprees of congress. The foreign lies and policies have become our domestic lies and policies, with more to come.

Editor’s Note: If you would like to reach Mr. Leavitt directly, you can email him at dave.j.leavitt@protonmail.com.

5 replies on “Our Foreign Lies & Policies have become our Domestic Lies and Policies”

That was very well written and informative, thanks for a lot of true information

Yup. Same as my war- Viet Nam. propping up racketeers at war with thier own people, creating more implacable enemies with every massacre we visited on those people, with the same utter lack of honesty about why we were there and what we were actually doing, very different from the bullshit flooding public discourse.

Very informative and well written article. 1st. Thank you for your service to our country. You are a true Patriot. 2nd. Yes it is sad to see how our country is resembling some of the same government overreach that happened to the people there. God bless you and our country.

Very well written.

One does not know how others live unless they have walked in another’s shoes.

Thank you for taking the time you took to write and to educate all who may read your experiences.

Thank you for your service.

So where do we go from here?

Get the US out of the United Nations for starters! Support HR204! The UN is the source of most of our problems at home and abroad.