Despite years of opposition, that virtually no one wants this in their backyard, and that all Magic Valley County commissioners have publicly opposed it (you can read MVLA’s report here) Biden’s Bureau of Land Management announced on December 6 it has approved the Lava Ridge Wind Project northeast of Twin Falls, Idaho. Read BLM announcement.

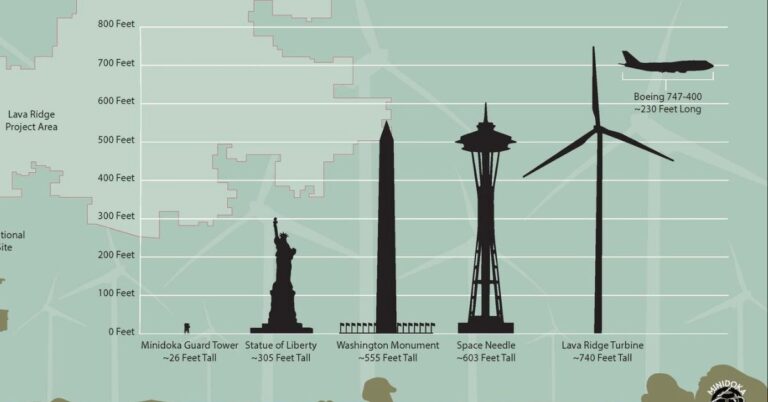

According to Idaho Dispatch, BLM’s 231 massive wind turbines could be placed on approximately 60,000 acres in Jerome County, Minidoka County, and Lincoln County. The height of the turbines would not be allowed to exceed 660 feet, which is still more than double the height of the Statue of Liberty. Read Idaho Dispatch report here.

The Good News: A New Legal Pathway for Challenging the Lava Wind Project

By Rebecca Smith, December 9, 2024

As large-scale projects such as the Lava Ridge Wind Project in Idaho move through the federal approval process, concerns about their environmental, social, and economic impacts continue to grow. Legal challenges to these projects are increasingly focused on how federal agencies interpret and apply regulations, and recent developments in U.S. Supreme Court decisions could play a critical role in shaping the future of such projects. Specifically, the 2024 Supreme Court ruling in Loper-Bright Fisheries v. Raimondo marks a significant shift in how courts may approach Chevron Deference and could provide new legal tools for challenging the Lava Ridge Wind Project.

The Evolution of Chevron Deference

Chevron Deference has long been a key principle in administrative law. Originating from the 1984 Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. case, the ruling established a two-step framework for determining when courts should defer to an agency’s interpretation of an ambiguous statute:

- Step One: If the statute is clear, courts apply the statute as written. If ambiguous, then:

- Step Two: Courts defer to the agency’s interpretation as long as it is deemed reasonable, even if there are other possible interpretations.

This doctrine has allowed federal agencies like the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) significant discretion in interpreting and enforcing regulations, including those governing large infrastructure projects such as the Lava Ridge Wind Project. However, Chevron has faced criticism for providing agencies with broad interpretive power, particularly in cases where the consequences of agency decisions are wide-reaching.

The 2024 Supreme Court Ruling: Limiting Chevron Deference

In 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling in Loper-Bright Fisheries v. Raimondo, significantly altering the landscape of judicial review of agency interpretations. In this case, the Court questioned the continued applicability of Chevron Deference, particularly in situations where agencies make major policy decisions that could have significant economic, environmental, or social effects.

The Court held that Chevron Deference should not automatically apply when agencies make decisions that involve broad regulatory or policy shifts with far-reaching consequences. Specifically, the ruling emphasized that in cases where the stakes are high and the potential impact on the public is significant, courts should not automatically

defer to agencies’ interpretations. Instead, they should engage in more rigorous judicial review to ensure that agencies do not exceed their authority or make unreasonable decisions.

How the 2024 Ruling Could Affect the Lava Ridge Wind Project

Opponents of the Lava Ridge Wind Project, particularly local residents and

environmental groups, may find the 2024 ruling in Loper-Bright a valuable tool for challenging the approval process. The project, which involves significant land use and has potential implications for local wildlife and communities, could be seen as exactly the kind of case where the Supreme Court’s rethinking of Chevron Deference applies.

Limiting Agency Power in Major Regulatory Decisions

The Loper-Bright ruling stresses that agencies should not have unchecked power when making decisions that affect large groups or have major policy implications. In the case of Lava Ridge, opponents could argue that the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or other federal agencies have overstepped their authority by granting approval to the project without fully considering its large-scale environmental, economic, and social impacts. Given the scale and consequences of the project, challengers could argue that the Court should not automatically defer to the agency’s interpretation of laws like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) or the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

The ruling in Loper-Bright suggests that decisions on such projects should undergo closer scrutiny by the judiciary, especially if there are concerns that the agencies have interpreted the relevant statutes too leniently or failed to account for the broader consequences of their actions. This could significantly strengthen legal challenges to Lava Ridge.

Challenging Ambiguous Agency Interpretations

One of the key elements of the 2024 Loper-Bright ruling is the Court’s emphasis on limiting the scope of Chevron Deference in situations where statutes are ambiguous, but the agency’s interpretation may have a significant impact. In the case of Lava Ridge, opponents could argue that if the BLM or other agencies interpreted environmental statutes in a way that minimizes environmental reviews or overlooks key concerns such as wildlife protection, these interpretations should not be automatically accepted by the courts.

If agencies rely on ambiguous or overly broad interpretations of laws to justify the project, challengers could invoke the 2024 Supreme Court ruling to argue that courts should not defer to the agency’s decisions. This is especially important in cases where the public and the environment could bear the brunt of such regulatory decisions.

Requiring More Judicial Scrutiny of Agency Decisions

The 2024 Loper-Bright decision also reinforces the need for greater judicial scrutiny when the regulatory decisions involve substantial impacts on local communities, businesses, or the environment. Given that the Lava Ridge Wind Project could disrupt local wildlife habitats, land use, and Indigenous cultural sites, opponents could argue that the decision to approve the project requires heightened scrutiny. Courts should closely examine whether the agencies involved have properly considered all relevant factors and have acted within the bounds of their authority.

In light of the Loper-Bright ruling, critics of the Lava Ridge project can make a stronger case for judicial oversight, suggesting that the decision to approve such a large-scale infrastructure project should not be made solely by the BLM or other agencies without robust judicial review to ensure that the public’s interests and environmental protections are adequately addressed.

Conclusion: Strengthening Legal Challenges to Lava Ridge

The 2024 Supreme Court ruling in Loper-Bright Fisheries v. Raimondo has reshaped the application of Chevron Deference, particularly in cases where agency decisions have major policy implications and affect the public in profound ways. The ruling limits the scope of Chevron by making it clear that courts should not automatically defer to agencies when the consequences of their decisions are significant.

In the case of the Lava Ridge Wind Project, opponents can use the 2024 ruling to argue that the decision to approve the project should be more rigorously examined by the courts. The Loper-Bright decision provides a strong legal framework for challenging the agencies’ interpretations of environmental laws, such as NEPA and the ESA, especially when the consequences of those interpretations could be detrimental to local communities and the environment.

By invoking this new legal precedent, challengers can argue that the regulatory decisions made by the BLM and other agencies involved in the Lava Ridge project should not be shielded from judicial scrutiny. Instead, these decisions should be carefully reviewed to ensure that they align with statutory intent, properly consider the full impact of the project, and do not exceed the authority granted to federal agencies.

2 replies on “Lava Ridge Wind Project Update: First, the Bad News.”

The Energy Act 2020, Section 3104 lays out national goals for renewable energy on federal land. Mapping for solar and wind projects have already been completed with exceptions listed for wind in the West Wide Wind Mapping project. A Wind PEIS has also been completed that identifies areas for Lava Ridge. It might be the BLM, and feds, have already laid the groundwork for this project. This agenda for renewable energy has been in play for a very long time, is a global energy takeover in which the DOE is involved, and executive action may be the only way to stop it, at least for now.

Thx Karen,

Agreed, the globalist’s energy takeover under the guise of the UN’s Agenda 20230 sustainable goals is being played out with Lava Ridge. Pray ID Attorney General Labrador’s efforts will be fruitful. My understanding is Lava Ridge is but one of several projects slated for ID, with Salmon Falls as #2.